A little over a week ago, I found myself pushing the couches together in response to a last-minute request from my kids for “the boat,” a term that originally referred to the formation of the couches themselves, but that has since taken on its own meaning as a complete overnight experience with dad, the kids, and the dog. We climbed in and had a blast being silly, eating lots of caramel corn, and watching Finding Nemo.

The film had us all in stitches. It had been many years since I’d seen it and, although I remembered the humor, I was struck by some of its themes: namely the need to trust, surrender, and stop living in the safety of our constructed worlds for fear of what lies on the outside.

These things were far more relevant than when I’d previously seen the movie and they resonated deeply as I reflected on the recent years of my life. Never once did I minimize the power of the messages because Nemo, Dory, and Marlin are characters in a fictional story.

It got me reflecting on a conversation I had a few years ago. I was wrestling with some things in my spiritual life and the “God said it. I believe it. That settles it.” bumper-sticker approach to a life of faith had long ceased making sense to me.

I was discussing some of the odd stories in the Bible with an extremely well-educated and successful man and he made a peculiar comment. He said “If there wasn’t an actual talking snake in an actual garden, we may as well throw the whole Bible out the window, because what good is it?”

Really? Okay, I realize to consider that any given story in the Bible didn’t really happen may bring about some serious uncertainty, but come on. Throw the whole Bible out the window if the snake didn’t actually talk? At the time, I wasn’t sure how to respond, so I just didn’t say anything.

This man’s attitude reflects a fairly common theme that I’ve been all too familiar with in the evangelical Christian community. It’s as though somehow the quest to know God and to experience spirituality must be tied to approaching the scriptures as “literal” representations of things that really happened. But do we ever stop to ask why that is?

Why does the truth of the Adam and Eve story hinge on the fact that there was a talking snake or a flaming sword suspended in the sky?

Does the thought-provoking narrative of Job lose its power if it turns out that God didn’t really give Satan permission to go unleash holy terror on Job’s peaceful existence?

And if Jonah didn’t actually spend three days in the belly of a fish, does that somehow cheapen the author’s message that God’s love and acceptance extend beyond the boundaries of tribal thinking? Beyond the mindset of “We’re in and they’re out”?

Stories have incredible power to touch, shape, teach, and even transform us, whether or not they ever “actually happened.” It’s the case for us today – as I witnessed while lounging in the boat watching as Dory implored Marlin to let go and fall into the scary, unknown depths of the whale’s throat – and I’m sure it was equally the case for the ancients, if not more so.

Myths and fanciful tales were how ancient people probed big questions, explained circumstances, and pondered the meaning of things. That’s simply how it was. A casual glance at the ancient creation and flood stories that pre-date the biblical accounts – which unfortunately many Christians don’t even know exist – make it pretty clear that those authors weren’t attempting to document literal history.

And before we write those stories off because they’re not “scripture,” we should acknowledge that the similarities with the later biblical stories make it clear that the biblical authors incorporated elements from these tales. In other words, the authors of the creation and flood accounts found in Genesis took established stories from surrounding cultures and molded them as they saw fit.

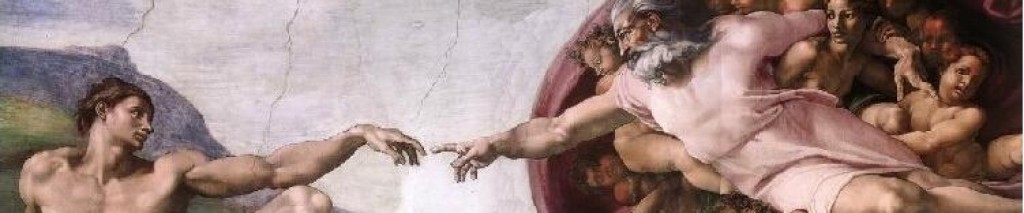

The poetic 7-day creation account wasn’t meant to offer scientific explanations or teach dogma to a nation of people. In part, it was to provide these ancients with an understanding of God that was different from what they had been exposed to. “Creation wasn’t the result of their deities warring in the heavens like that other story says; it was the result of our God speaking it into existence.” That kind of thing. God being said to rest on the seventh day doesn’t mean God got tired and needed a nap; it was a symbolic way of legitimating the nation’s existing Sabbath-day practices.

The idea that stories in the Bible are intentionally symbolic or rooted in myth doesn’t have to be scandalous, nor does it have to wage war against our faith. It actually stands to reason. It would be irresponsible to assume the biblical authors wrote in a manner inconsistent with what was common at the time. We may expect modern biographies, history books, and news sources to report “just the facts” – even though we acknowledge that they often don’t – but we shouldn’t approach ancient writings this way, because such expectations would’ve been simply foreign to the people of the day.

But it gets a bit tricky. On the one hand, we have no problem acknowledging the fictional elements in other ancient stories. Heck, often times, we shamelessly point them out and scoff in the process. Yet when it comes to the Bible, things are different. We’re more protective. It becomes oddly uncomfortable – perhaps even scary or threatening – to consider that the story of Jonah didn’t really happen. Because the natural question is where do we draw the line?

If a flaming chariot didn’t descend from the heavens to whisk Elijah away, or the sun didn’t really stand still in the sky until Joshua’s army was done decimating its enemies, does that open the door to the possibility that Jesus wasn’t actually born of a virgin? Of course it does. We don’t have to automatically make that leap, but there is a slippery slope that needs to be navigated.

And since most of us prefer the certainty of a sure footing, we try desperately to avoid the slope altogether (I’ve been there).

This is probably why some Christians believe that the devil planted fossils in order to trick us into believing evolution. Because for some people, if the earth is more than 6,000 years old, they’ve suddenly been shoved out onto the slippery slope. And if Adam and Eve weren’t two historical people who started the entire human race, what does that do to our worldview?

And so we become bent on proving the Bible is true (meaning that it all really happened). Or proving the Bible isn’t true, as some do. But people on both sides are barking up the wrong tree.

I’ve come to believe that “Did it really happen?” is simply the wrong question. Approaching the Bible in such a way is the wrong approach. And trying to prove or disprove it is futile and misses the point.

There’s much more to be said about all of this and I’ll explore it more later, but I’m pretty sure the original audience of the Adam and Eve story would never have considered throwing the scroll out the window if there wasn’t really a talking snake.

After all, if there wasn’t a talking snake – in fact, if none of the aforementioned stories actually happened – would God cease to be God?

And if so, perhaps the more pressing question is what kind of God are we talking about?

Leave a Reply